In May, the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated a quarter-century-old law that had banned sports betting in most of the country. [1] Three months later, a new football season will begin with states across the nation scrambling to launch legalized gambling houses. [2] While this change alone is unlikely to fuel the growth of casino-resorts, it is another move in the same direction as the advent of so-called Indian gaming. Taking advantage of the in-applicability of state law to reservations, many Native American tribes have built casinos on their land that rival those of Las Vegas and Atlantic City.

Albeit for different reasons, Indian gaming often revolves around casino-resorts. While the draw in the cases of Las Vegas and other gaming hot-spots is the allure of being in the mix of a world-renowned destination, in the case of Indian casinos the reason for staying overnight is often mere pragmatism – reservation land is often remote from major population centers, and after a night of gaming and imbibing it would be imprudent to drive home.

Whatever their genesis, casino-resorts turn out to be a safer place for employees than hotels without gaming. Now, this is an obvious proposition when one considers that there are many more non-casino hotels than casino-hotels and that the former employ many more people than the latter; it makes complete sense that there are more workplace injuries at the former than at the latter. [3] But even when accidents are calibrated on a worker-for-worker level, hotel-casino workplaces are safer on the whole.

The federal Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is probably best known for its measures of the U.S. economy, including the vaunted monthly jobs report. (If you’ve ever wondered what “seasonally adjusted unemployment” means, you have the BLS statisticians to thank for your puzzlement.) Among the many things that BLS collects data on are workplace injuries, specifically both fatal and nonfatal “Work-related Injuries and Illnesses Involving Days Away From Work.” [4]

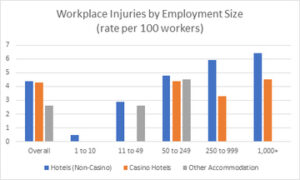

Size matters, as the BLS finds. The department keeps track of injuries by many measures, including the number of employees at the workplace. Injuries per 100 workers are more common (4.4 per year) in non-casino hotels than in hotel-casinos (4.3) and much more common than other kinds of “traveler accommodations” (2.6). [5] This is the case even in large facilities with 1,000 or more employees.

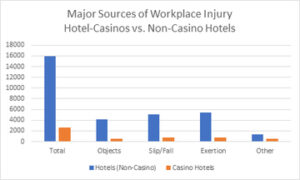

The BLS reports a total of 15,900 nonfatal incidents at non-casino hotels, with the largest share coming from overexertion (5,420). For hotel-casino employees, the total number of incidents was 2,350, with slip-and-fall accidents estimated as slightly more prevalent (820) than overexertion injuries (800). [5]

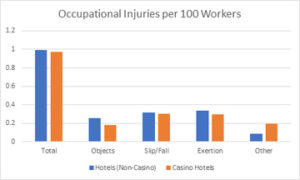

When the major causes of workplace injuries were weighted for the number of employees in each sub-sector of the industry, the comparison is much closer. While non-hotel casinos are nonetheless safer environments than hotel-casinos for most kinds of injuries, the difference becomes one of degree. And in the case of “other” injuries – a broad category that includes injuries due to transportation, fire and explosions, and violence from people or animals, workers at hotel-casinos are actually more vulnerable than their peers in non-casino establishments.

For communities like Las Vegas, these trends make the service sector a safer place to work on the whole. That is not to say that accidents do not happen and that their results cannot be devastating. Perhaps the contrary is true – perhaps the rarer workplace accidents in casinos are the greater threat to workers’ well-being and lives. We hope to explore this in a future post.

[2] https://www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2018/08/30/nfl-1st-season-legal-sports-betting